Forsaken Music and the Lure of the Solid

A visit to a used bookstore this summer was unexpectedly disconcerting. Out of the corner of my eye, I glimpsed a familiar book, of a smaller dimension than I’d seen before. At 6.25 x 4.25 in (16 x 10.5 cm), the green Lutheran Book of Worship wasn’t exactly pocket-sized, but it fit perfectly in my hand. It was a smaller, sturdy-softbound version of the hardcover tome stored in the back of the wooden pews in every church I’d attended up through adulthood, complete with thread binding, gilt-edged pages, and place-marking ribbons so well made that they hadn’t even started to fray between the time of the book’s publication in 1978 and my encounter with it forty-seven years later. This was probably a pastor’s copy, to have on hand for traveling or as a quick reference, easier to carry than the larger hardback. But considering it has everything (and maybe more) contained in the standard edition, the print can get pretty hard to make out—even impossible for me without reading glasses when trying to decipher footnotes.1

The church I grew up in held to a set liturgy/order of service. That’s different from, say, Quakers, who sit in silence until anyone’s moved to say something; or Pentecostal or many Baptist traditions, where there’s not necessarily a given pattern for how things proceed. We, though, would know every Sunday what was in store, following along in the bulletin or book, with some of the tunes or texts changed based on the time of year, and hymns different every week. The criticism of this type of service by many nonliturgical groups is not only that it can feel unwelcoming for the uninitiated, but that after a while, you could pretty much do it in your sleep, not even thinking about what you were saying or chanting or singing, and hence engaging in meaningless repetition.

There’s merit to that argument, but there’s also the eerie reality of what happened to me in that bookstore, thanks to a few decades’ worth of weekly common chant and prayer. I haven’t been an adherent of any religious tradition in at least twenty years, and even as I was coming to the end of my churchgoing days, the liturgy was starting to change, incorporating new wording, more contemporary music, and usually eliminating the chanting in favor of spoken responses and prayers. It wasn’t the stuff of many nondenominational churches, with praise bands and slides (and now PowerPoint versions) of lyrics projected onto a wall—but it was leaning toward Muzak and the sort of generic melodies you might hear playing quietly in the lobby of a therapist’s office.

Though it was often uninspiring, even annoying, to hear these more simplistic tunes, it wasn’t the watered-down music that had me creeping for the doors; it wasn’t even the “theology,” if we’re talking about how different Christian traditions interpret a very broad inheritance (which has itself been contested ever since the get-go). It was instead the fact that I just didn’t believe what was on offer even generally, and so couldn’t sit (or stand or kneel) there and profess a lot of stuff I didn’t accept.2 And so it was unnerving to say the least to feel the emotional pull of this beautifully sized volume and to hear the entire service in my head, and to know that I’d still be able to chant, speak, and sing the entire thing from memory. It was even stranger that, after an hour in the store, and multiple walks back to look at what I’d always just called the hymnal, I gave in and bought it.

There was a yearning for something here, obviously—maybe just the pull of nostalgia. But nostalgia for what? Yes, the church had been just as central as school or my neighborhood to social life, and had contributed at least as much (contrary to the ugliness on display today from so many self-professed Christians) to learning how to walk responsibly and respectfully through the world. But it wasn’t as if there’d ever been anything particularly golden about church get-togethers in themselves; my sarcasm was honed early on by neo-hippie Sunday school materials (chill-looking watercolor disciples and JC just digging the Galilean vibe) and the continuum of cheesy-to-too-pious behavior at potlucks and coffee hours and camp. The pull, I’m convinced, was musical.

I wanted at first to say “purely musical,” but that’s not quite right, or complete. Instead, it’s the collective musicality I miss, the way this particular collective approached it, and the quality of what we were giving ourselves over to. Let’s see if I can explain.

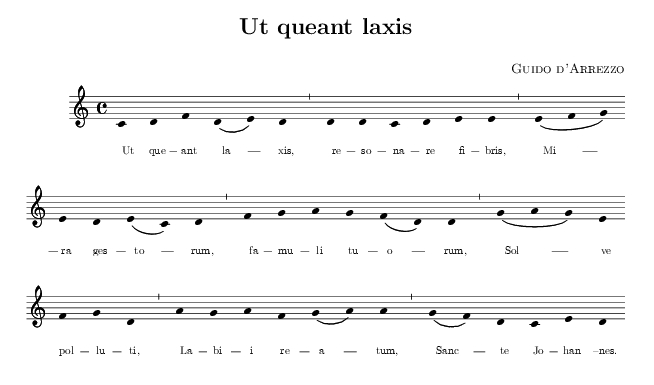

What’s central here for me is the chanting. So for example, to start the service, the pastor might offer a brief good morning or a welcome to everyone present, but then we’d get right into it, with musical notation available in the LBW or sometimes printed out in the bulletin to follow along, the pastor intoning a petition and the congregation chanting back its response. Before and after (sometimes during) textual readings, the same would happen; prayers would be recited together; things would be sung back and forth before and after communion; hymns would be belted out or struggled through along the way; before we were dismissed, the pastor would intone a benediction. Except for the sermon and recitation of some prayers and maybe the Nicene or Apostles’ Creed, there wasn’t a lot of spoken, as opposed to sung, communication going on. Within it all, you could even have taken out most of the hymns, and I would’ve been OK. As I said, it was that close-to-plainsong intonation that got me.

The contemplative aspect is undeniable, thanks especially to what essentially amounts on the pastor’s part to an a capella soloist carrying everyone through an hour or so. And there’s also something comfortingly arresting about a whole group of people singing the same thing, without (as is possible in multipart hymns) anyone grandstanding and veering off into showy descants. It may be one of the closest things I’ve experienced to doing something together, and doing it for no purpose other than to do it—not, say, as part of a performance or competition, or even as practice for one, as is usually the case with a choir.3 In a loose, though not meaningless, way, that sung petition-and-response can give rise to a feeling of connection, maybe even belonging, even if temporary. It is easy to lose yourself in the singing and recitation, not even thinking about what’s coming out of your mouth. But that, too, is grand—a letting go that in any other scenario might be condemned as the equivalent of unproductive staring out the window, a lapse from strategizing about how to get to the next point along your path to personal (or spiritual) success.

The other thing is that, especially for a lone and probably untrained soloist out there in front of rows full of people staring back at you, chanting that music is a daunting prospect. Try singing out an unaccompanied sentence on the same note, staying on pitch the entire time, switching back and forth between often-odd intervals, and then having church ladies and bored and snarky teens judge you on your tone, and you might be eager just to speak the whole thing. Even if you have the notation before you, and even if you’ve heard the music week after week for most of your life, the probability of flubbing it is real. All that is true: and all of it is involved in what so often makes the result quietly stunning. The music here is good, not easy. It’s a demand that, even as you know nothing is at stake or will be gained—maybe because of that fact—you do your best to deliver something of quality, something that will put a little beauty into the world, instead of more of the jingly pabulum floating around everywhere else.

The difficulty and quality involved in the music, the need, even if you’ve heard it all your life, to keep an eye on the notation to help you stay in tune, the fact that you may sing the same damn thing without (much) change every week of your life, gives that song a solidity and depth that praise music and religious rock, with their simple tunes and repeated, empty phrases—predictable, somehow corporate, easy to learn after one verse and somehow indicative of impatience or an attention disorder at the same time—never had for me. Christianity gets touted as something that denigrates the materiality of the here and now, concerned instead with whatever disembodied reality ostensibly comes after we’re dead. Maybe that’s why so much praise music feels flimsy, and today, like good digital consumerism: each song sounding pretty much identical to all the others that just keep blaring the same few lines over and over, tossed off and forgettable—just like every other part of our earthly life is supposedly a worthless, disposable prelude to what comes next. Why spend much time on it? Because there’s no performance, and none of our skills or accomplishments or achievements matters to God, why bother with really getting it down, or making it harder than it has to be? That’s just celebrating worldliness, instead of looking toward the next best thing.

When I took that green book off the shelf, that may have been what I felt: an odd solidity, and a yearning for it that I knew couldn’t be fulfilled, not really; for that, I’d have to believe in what was bringing a congregation together in the first place, and ignore the ways in which that pull really doesn’t seem to make much difference to how most people act or think after they step back out into the world. For a while, I did try to keep going to church for the music alone, and to let the rest, as my mother often says, go in one ear and out the other. But I, and my presence there, just felt too dishonest to keep up the charade. I was never able to succumb to the process of, as many a religious adherent would insist is possible and necessary, sticking with it until you wind up convinced or converted. Nor has anything like the assertions of Don Gately’s AA sponsor in Infinite Jest ever worked or sounded any better, namely “that it didn’t matter at this point what he thought or believed or even said. All that mattered was what he did. If he did the right things, and kept doing them for long enough, what Gately thought and believed would magically change.”4

At best, what I can appreciate, and what might be the sort of solidity that could be the closest, or only, thing really on offer, is the way Kathleen Norris describes the monastic life in Dakota:

Ora et labora, pray and work, is a Benedictine motto, and the monastic life aims to join the two. This perspective liberates prayer from God-talk; a well-tended garden, a well-made cabinet, a well-swept floor, can be a prayer. Benedict defined the liturgy of the hours as a monastery’s most important work: it is, as the prioress explained it, “a sanctification of each day by common prayer at established times”…. It may be fashionable to assert that all is holy, but not many are willing to haul ass to church four or five times a day to sing about it. It’s not for the faint of heart.5

Work well done, and a sanctifying of each earthly day lived in the here and tangible now through that work: time taken to do the work, to do the singing, right. To take the time to give it your best, and to recognize value in that ponderous giving. That’s the sort of solidity I think I was reaching for when I took possession of an unfashionably durable relic known as a printed, carefully bound book, a book meant to last. Not the solidity of existential certainty or predictability or a cessation of change. Rather, something to counter or provide a center to the experience of being surrounded on all sides with an obsession with efficiency; with innovation and the needless breaking of things to accomplish or toy with it; with getting a computer to do for you as much as possible, so that you don’t have to do the work, whether in the form of thought, practice, or physical or other labor, yourself.

This morning, I turned my little book to the opening invocation and sang to the early light and the silence, managing to keep in tune for the most part and hitting in others too flat or sharp. It won’t send me back to church or the beliefs that prop it up, or even get me in the habit of chanting every morning from here on out. But it was good to be singing for no reason, and to hear my shaky voice trying to get it right, wasting no time at all as the world woke up around me.

1. There was a name inscribed on the title page—and as I flipped through, an old business card fell out. In the center was “L.A. SWANSON Retired,” and on each corner, “No Address,” “No Phone,” “No Money,” “No Business.” A search for anyone by this name only came up with 1985 article in the Chicago Radio Guide, but there was no mention there of pastoring or anything related to it. Geographically, it made sense, since I found the book not too far away, in Davenport, Iowa. For the curious, the article was “Station Spotlight—WCEV, Chicagoland’s Ethnic Voice, Speaks to All Americans,” Chicago Radio Guide 1, no. 1 (May 1985): 10, 110–12, https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-Other-Documments/Chicago_Magazine/Chicago-Radio-Guide-May-1985.pdf.↩

2. Pretty simple, and much to many contemporary apologists’ disappointment, it wasn’t because I’d been “hurt” by anything I found or that happened to me in church, or because it was boring, etc. And this is an essay for another day, but my leaving seems in part to have been due to the fact that I actually thought I was supposed to take the ethics supported by my particular tradition—broadly, to treat fellow creatures, human and non-, as well as the earth itself, as Kant might have said, as means in themselves, and never ends—seriously, and not as a performatively tossed-off creed.↩

3. Admittedly, the official purpose of even being there at all isn’t just to carry out the motions for their own sake; the point is the motions constituting worship. But still.↩

4. David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest (Back Bay Books, 1996), 466.↩

5. Kathleen Norris, Dakota: A Spiritual Geography (Houghton Mifflin, 1993), 185.↩