Gamy Calculations

A placement test, these days at least, is a curious thing. It’s not that some sort of one-time attempt to measure your knowledge of a subject hasn’t always been a bit suspicious; a bad night’s sleep or a case of hay fever or even a less-than-friendly proctor could mess up your reasoning so badly, your official exam result would make it appear as if you’d never even heard of the subject in question. Probably since at least the turn of the millennium, though, trying to get a handle on an aspirant’s true abilities in one particular area has become the responsibility of a computer program.1

Here’s what I mean: the placement test I took this week was done on a screen, where some of the potential trip-ups had to do with simply understanding how to input your answer. Then there was the fact that the test was adaptive: provide a correct answer, and you get moved on to something more challenging; get the question wrong, and you’re taken to an easier problem. Already, we’ve got at least two sources of nerve-racking: there you are, trying to figure out which icon to click to make a graph, worried that you’ll hit the wrong thing and it’ll send you off into wrongland—upon which you’ll be presented with the next problem, a death-dealing simple demand to say what 2+5 is, and there go your chances. There’s no human examiner lurking behind the screen, able to see the proof you’ve worked out on your scratch paper, the very proof that shows you understand what’s going on, save the negative sign you forgot to write in. Nope: unlike in the math classes I had up through college, the answer in this scenario—not your understanding of it, how you got it, or whether you arrived at it by luck—is the only matter that counts.

Thankfully, whatever I did on my placement test counted enough to get me into the class I wanted. But I know there’ll be more math to come, and even though I’ve satisfied all requirements for now, it would be laughable to say that I understand what I’m doing, much less feel comfortable with it all. And so I’ve taken up the testing system’s offer of free math review for the next year; I can even attempt to place out of further requirements as I go along. Super; why not? I’ve got nothing to lose but time and a sense of my own capability.

For the past few days, then, I’ve been going up against the system’s precal conundrums. For each section, correctly answer a certain number of questions in a row (usually it’s two or three), and the screen flashes out some LinkedIn-style hyperbole (“Superb!” “Magnificent!”) to let you know you’ve “mastered” a topic, and I guess to encourage you to keep going. Hey, I managed to pull out two right answers: I’m a winner! I should be proud of myself!

The thing is, in spite of what the e-confetti and balloons have been asserting, I most certainly have not mastered logarithms, nor have I managed to break through my lifelong impairment in setting up equations when given a word problem. I suppose I’m at least getting a bit of practice at somewhat blindly working through problems, but other than that, confusion abounds about what the point of this particular arrangement is; right now, I suspect all the celebration is simply meant to make me feel good about sitting down and trying. In itself, that’s not a bad aspiration, especially if you consider the years’ worth of math baggage I’m still carrying around. But all that feel-goodiness seems so far to be leading around the same circle of doubt and discomfort, and I can’t even tell you what the distance around that circle is in radians.

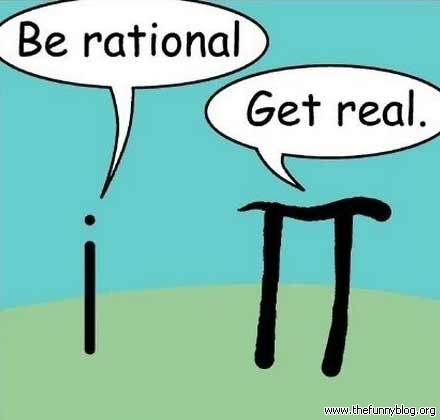

And so we come to at least one of my long-term beefs with the gamification of seemingly everything, but especially with learning. Were the system to take me seriously, it would provide me with some plain-language explanations of the concept at hand, and would stop flashing canned graphics at me every two minutes, as if the lure weren’t eventual understanding of a particular idea or process, but simply more shiny objects, the equivalent of the food pellet the lab animal gets if he presses the right lever. Author and game designer Ian Bogost’s denunciation of corporate gamification, whose systems he chooses to call “exploitationware,” seems spot-on: “It offers simple, repeatable approaches in which benefit, honor, and aesthetics are less important than facility.”2 Or in other words, the fancy superlatives and clip art I’m being blasted with are more important than my understanding what to do with a function.

This sort of set-up has me thinking of philosopher Susan Neiman’s criticism of much current euphemism. The well-meaning intention to avoid hurting others with the language we use often does nothing, she says, to show us the terrible situations we’re actually dealing with—and if we can’t see the reality behind them, we probably won’t be motivated to change them. “But an unhoused person,” Neiman says,

is no better off than a homeless one; if anything, the softened language makes the condition sound less painful. Being homeless is deeper, and worse than being unhoused, and the hardness of the language reflected that. Similarly, “enslaved person” takes the edge off the condition of slavery. Though we need no reminders today, those who bought and sold men and women did not consider them to be persons. Sometimes language should hurt as much as the circumstances it denotes; otherwise it is false to the realities it names.3

Temper the language, and it seems there’s really not so much to be lamented, and so nothing that needs urgently to be done; the unhoused, after all, have just as much “agency” as anyone else. Make the hurt plain, on the other hand, and it becomes harder to feel we can avoid doing something about it. In the far less troublesome arena of my math study, all the hurrahs would seem to convey the fact that I’m doing just fine, and instead of getting the help of someone who understands what my brain’s hang-up is with proportions—instead of considering the possibility that there really might be something lamentably odd going on with my cognitive m.o.—I just need to give a certain type of equation another go. You’ve got this!

It’s not that I want my inhuman math tutor to insult me in traditional fashion when I get a problem wrong, as in “You idiot; how did you even get to this level of tutorial with an answer like that?” It’s instead that the program is already mocking me by handing out the equivalent of participant ribbons everyone got at the mandatory elementary school track meet, even the kids who just sat on the sidelines. In trying to keep my morale up, this sort of curriculum is instead making me wonder if I’m being tricked into wasting my time, while the company behind it racks up the bucks for every minute I spend “interacting” with it.

Maybe I’m just another cynical Gen-Xer. We were, after all, treated in high school to Channel One, a deal the teens and teachers could see right through, but apparently not the administration that purchased the package. The transaction went like this: the school signed a contract with the Channel One people; the latter would hook up TVs in all the rooms, but only with the nonnegotiable understanding that at a certain point in the day, we’d all have to take ten minutes out of our actual learning time and watch the fake-serious news summary-and-commercial combo that we all rolled our eyes at, bucking against the indignity of it all. Here’s how educational theorist Michael Apple, writing while I was headed into my junior year of high school, described it:

When a school signs a contract for Channel One, it receives a satellite dish, two central VCRs, and 19-inch classroom color televisions. The equipment is provided, serviced, and maintained at no cost to the school—as long as the school receives Channel One.

Schools, in turn, must guarantee that 90% of the pupils will be watching 90% of the time. The 10 minutes of “news” and two minutes of commercials must be watched every school day for 3-5 years. There’s another catch: the satellite antenna is fixed to the Channel One station and cannot be used to receive other programs. Further, schools only have use, not the ownership, of the equipment. If the contract is not continued, the equipment can be taken away.4

There’s a lot of fantastic discussion in Apple’s article about conservative efforts to defund education, move to for-profit institutions, and replace taxation and etc. with business partnerships—all of which I’ve seen plenty. But those idiotic ten minutes at my high school were spent in pretty much the same way Apple describes some of the force-fed classrooms dealing with the intruder: ignoring, or more often in our case, making fun of, the pablum. It was the best we could do, because we had no choice. We realized our time was being sacrificed for someone’s financial gain, one more way in which the powers-that-be thought they could use our own tastes to fool us into handing over something they wanted. An early version, in other words, of exploitationware.

But that exploitationware is here to stay, because we’re not going to invest in human tutors, proctors, or exam graders for every student who needs them. If that’s the case, then could we at least hope for something a little less mendacious? While grumbling at the screen this week, I remembered the way a friend’s Wii Fit would let you know you hadn’t got the hang of its virtual skiing or dancing game: between one view of my avatar, which started out as an open-mouthed breather with Coke-bottle glasses, and the next, which followed my tripping over my own feet on the virtual slopes, said avatar had gained a muffin top and received the announcement, “Oh, you are not so fit.” Within the game’s universe, that was definitely true. We all had a good laugh at Nintendo’s willingness to risk its players’ good feeling, and got back on the pixellated slopes, undistracted by in-game applause at having put our boots or skis on correctly. But then again, there was nothing riding on any of this fun for fun’s sake; unlike mastering inverse functions, it really was just an honest game.

Subscribe to Off-Modern Onions!

You can subscribe as well via RSS feed.1. The first time I took the GRE, ca. 1996, it was on paper. When I went back for another round in 2003 (because no score could possibly remain reliable between those two dates!!), being granted the paper option was next to impossible, and I took the thing on a computer.↩

2. Ian Bogost, “Gamification Is Bullshit,” Ian Bogost, August 8, 2011, https://bogost.com/writing/blog/gamification_is_bullshit/.↩

3. Susan Neiman, Left Is Not Woke expanded and updated edition (Hoboken: Polity, 2024), 160–61.↩

4. Michael Apple, “Channel One Invades Schools,” Rethinking Schools 6, no. 24, Summer 1992, https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/channel-one-this-is-bad-news/.↩