Looking Back on Boosters of the Machine

It’s not as if tech-bro fantasies and consumption-related notions of the good life sprang up out of nowhere when the internet burst onto the scene. And it’s not as if the US only turned into a grand shopping mall, the “pursuit of happiness” equated with owning stuff, during the post-WW2 boom. But as good books are wont to do, Leo Marx’s The Machine in the Garden has been providing me some needed reminders about this here country’s long commitment to practicality as morality, and morality as material progress.1

Originally published in 1964, Marx couldn’t possibly have envisioned the digital cliff we, depending on your view, have either already tumbled over, or are about to leap off of with a joyful cheer. But his account still provides a solid review of how we got here. He starts with an early US celebration of the pastoral ideal, which adapted a classical Greek and Roman appreciation for some golden balance between untouched nature and too much civilization. The image of the noble shepherd in his field grew for the founders, Jefferson especially, to take on the sense of self-sufficient farmers scattered all over the place and enjoying the rural scene without having to break their necks working all day, and without having to work for someone else. (As has already been hashed and rehashed, though, whatever your version of the ideal, it was pretty rich coming from slaveholders, whether ancient Roman or colonial American.)

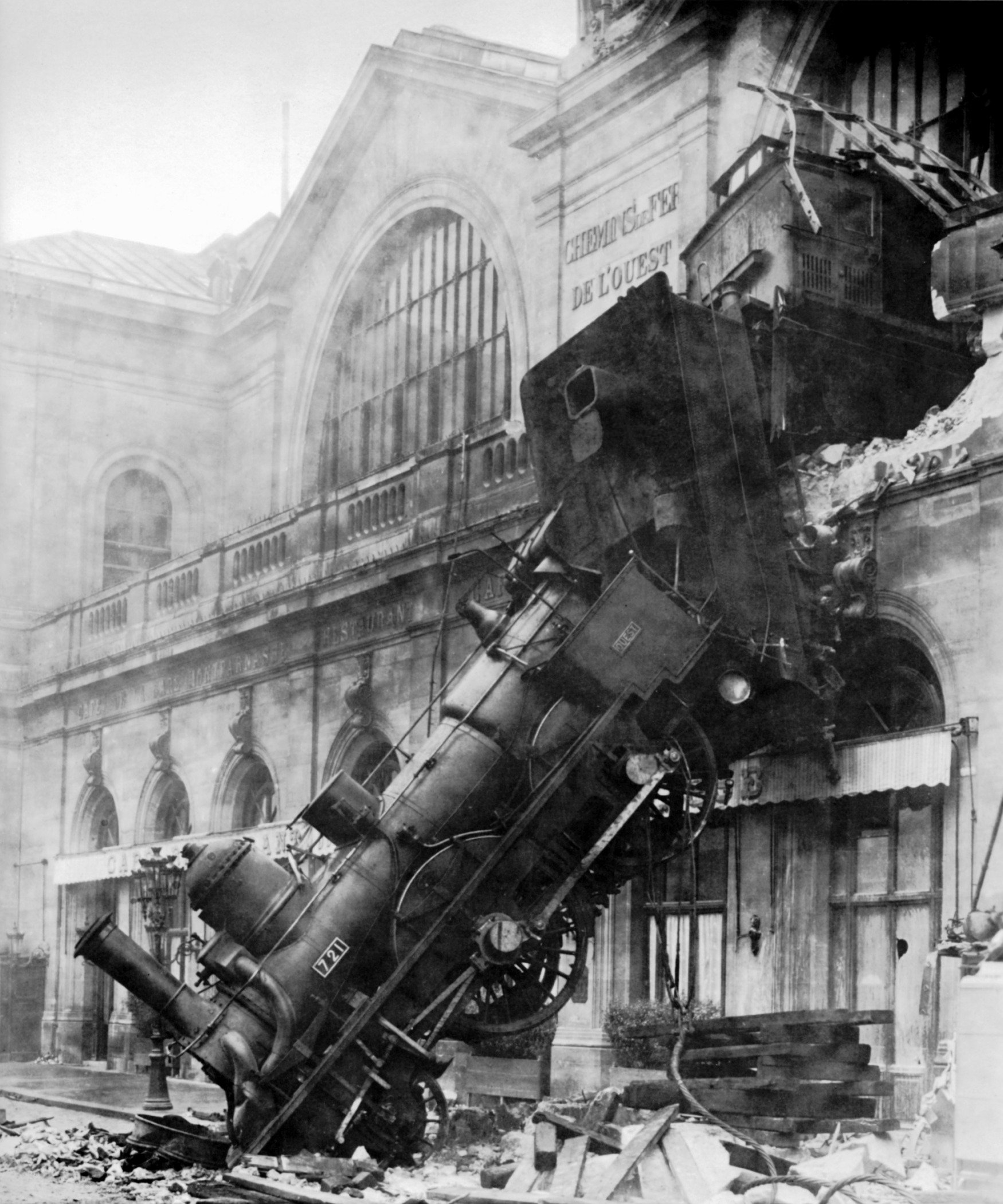

But then the machines—especially the railroad—came along, and though some bones about our sacred rural roots were tossed out at first, it didn’t take long before boosters of progress and business had consigned the old image to the dustbin: by the mid-nineteenth century, we were off and running and laying down track and wrangling steam, speechifiers like Daniel Webster whipping up everyone’s enthusiasm about the “miraculous era” and all the treats it would afford every last one of us.2

Again, this account is nothing new. But I was brought up short by the sentiment and wording included in one of the enthusiastic contemporary articles Marx quotes from. Out to pooh-pooh Thomas Carlyle’s lamentations about where industrialization was heading, in 1831, lawyer Timothy Walker describes Carlyle’s supposed pessimism as a bunch of “cheerless conclusions.” “Now where, asks Walker, ‘is the harm and danger’” of blasting through mountains and “apply[ing] the roller” to “uncomfortably rough” parts of the earth? Carlyle he says, is oh-so-worried “that in our rage for machinery, we shall ourselves become machines.” But look, says Walker, where we’d be without technology: living like brutes without “enough time to think,” and without any time to think, there’d be none of your precious culture to enjoy. He wraps up by asserting that "That nation… ‘will make the greatest intellectual progress, in which the greatest number of labor-saving machines has been devised…. [where] machines are to perform all the drudgery of man, while his is to look on in self-complacent ease.’"3

Sure, this is a familiarish socialist and/or utopian dream of having to work only so much, and then be able to pursue our interests and cultivate ourselves, etc. But in one of those episodes that makes you realize just how similar sentiment or assumptions or whatever can feel over the span of more than a century, it was the “cheerless conclusions” that first felt eerily familiar, and the unironic “self-complacent ease” that seemed completely contemporary.

When I entered my PhD program, all incoming students had to take a “transdisciplinary” course. It was a lot of mush forced upon us by a funder who badly wanted to find an easy way for scientists and businesspeople and poets and historians to talk to each other, and a university eager to take the (I think) ten million dollars on offer to do so. But as usually happens with these sorts of things and the hasty way in which they’re tossed out, no one really thought what it would involve to get people who’d spent most of their adult lives living into the norms and vocabulary and assumptions of one discipline to set it all aside and sing kum ba ya and iron out all their differences with others from different disciplinary worlds. There were a lot of arguments, and a lot of incredulity—summed up for me by an exchange with a business student. He’d been praising Toyota’s just-in-time assembly line practices as super-efficient, highly profitable, etc., etc. All I got in response to my bringing up the absolutely cruel conditions that existed on those assembly lines, and my question about whether work and enterprise should consider more than maximum profit, was the jokey dismissal, “You ethics people are so doom and gloom!”

I guess. But what felt to me then and now like complacent acceptance of the good life for company execs and the owners of Toyotas, while the people who built them probably wondered what the hell all of this bathroom-break-free life was for, has only become more obvious as we’ve moved from the Friendster age of then to the (generative) AI age of now, holding as it does ever more clingily to the dream of “machines” assuming human functions. We let the robots take over so that we can do what—sit there and stare at more stuff on our screens to buy? Walker’s vision of people hanging out and looking with “self-complacent ease” at the machines doing all their work might as well serve as the motto of these AI dreamers, whose own vision of what all this human replacement is supposed to lead to is still beyond me. All I can picture is a bunch of pasty dudes sitting on their asses in front of multiple monitors, celebrating the fact that they (or their chatbot) has just owned someone of a different gender and/or with a different viewpoint.

Their celebration of “freedom” and of being able to connect and follow your interests thanks to algorithms and so forth sounds a lot like Walker’s allegations about having time to think—only thinking is apparently not what he or anyone spouting all this glorious stuff is doing. Walker couldn’t see the harm in trashing the natural world or burning a lot of coal to zip across the continent on the railroad; the bros either can’t see or don’t care about the inordinate amount of energy and water being wasted on training AI to change your face into a cartoon character’s, or about who’s making sure all their same-day deliveries get made and what sorts of (human and environmental) conditions guide those supply chains. Yes, all the gadgetry was and is neat and unprecedented—but if anyone stopped to think about what its use could mean or lead to, whether there wasn’t something more important or meaningful to do than sit around and play video games, we’d at least have to slow down.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m no fan of work for work’s sake, or the moral uplift of pointless labor, or most of what passes for acceptable conditions of employment or so-called career options. But when the assumption is that none of us wants to do the things the bros don’t want to do—take the time to write their own sentence, much less an entire essay or book; care for a patient or loved one; spend years mastering an artistic technique or boat building or a musical instrument; help a patron or customer find what they’re looking for; cultivate your own food or make your own clothes or live sufficiently, and not surrounded by piles of stuff—our options for how we hope, not even to make a living, but more importantly to live our lives, continue to disappear.

I’m living into my ethicist nature, though, and bringing us all down, when the point of progress (or innovation, as we’d probably say these days) is to keep going, at all costs and with all possible speed. (What if someone else beats us to the next great thing?) As Marx notes, Walker dismissed the “premonition of mankind’s improving capacity for self-destruction,” the possibility that there was something to what he called Carlyle’s anxiety about “whether or not ‘mechanical ingenuity is suicidal in its efforts.’”4 But when so much of that anxiety would prove well-founded in the destructive twentieth century, and when so much more of our lives are being intruded upon by newer “machines” in the twenty-first, it’s well worth Marx’s look back on all the tech-centered cheer and sneer that was happening in the nineteenth.

1. Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, 25th anniversary ed. (Oxford University Press, 2000).↩

2. Marx, 214.↩

3. Quotations in this paragraph are from Marx, 182, 183, 182, 183, 184.↩

4. Marx, 184.↩